You can now find the Essex Law Research blog at its new homepage on the University of Essex blog:

Essex Law Research Team – University of Essex Blog

We look forward to welcoming you there for new posts, insights and updates from our researchers.

You can now find the Essex Law Research blog at its new homepage on the University of Essex blog:

Essex Law Research Team – University of Essex Blog

We look forward to welcoming you there for new posts, insights and updates from our researchers.

The EU-CIEMBLY project organized an internal staff training workshop from November 4th to 6th at the Universidad Complutense de Madrid, Spain. The primary goal of the workshop was to advance and harmonize the partners’ understanding of the theoretical and analytical framework, essential for designing and implementing an inclusive and intersectional European Citizens’ Assembly (CA). The event aimed to equip the project team with both normative tools and empirical insights essential for creating an inclusive deliberative process throughout the project. Dr Anastasia Karatzia, Dr Niall O’Connor, and Dr. Sam Woodward represented at the workshop the University of Essex team, which also includes Dr. Rebecca Warren and Prof. Ileana Steccolini from Essex Business School.

The workshop’s agenda included various presentations and structured discussions designed to engage participants deeply with key project objectives. The first segment of the event provided an introduction to intersectionality, a conceptual framework that examines the interconnected nature of social categories such as gender, nationality, ability, age and more, and how they combine to affect individuals’ experiences of inequality and exclusion. Participants engaged with this concept to explore how intersectional equality, inclusion, and deliberation could be effectively applied in the design and implementation of a CA.

Following this, the participants explored the three key components of a CA which are governance and organization, sampling and recruitment, and deliberation and facilitation. Break-out group discussions were featured, where participants were divided into smaller groups to brainstorm ways to enhance intersectional equality and inclusion across the various stages of the CA. Facilitators documented the insights shared during these discussions and later presented the findings to the broader group for collective reflection.

On the second day of the workshop, four theoretical models for an intersectional CA were discussed in detail, with the understanding that these could evolve based on ongoing feedback and the evolving needs of the project. The workshop concluded with discussions on the development of the glossary with complicated terms along with a presentation of the project’s language policy to guarantee that all materials and discussions are accessible and inclusive.

A few words about the project:

The EU-CIEMBLY project started on January 1, 2024, with the main goal of creating an innovative and inclusive EU CA that addresses issues of intersectionality, inclusiveness, and equality in European Union political life. The project seeks to improve the landscape of participatory and deliberative democratic mechanisms firstly by providing an analytical framework and prototype for establishing the Assembly at the European Union level, with potential for adaptation at national and local levels of European Union Member States. The project draws on an academic and theoretical understanding of intersectionality, equality, and power relations. Furthermore, EU-CIEMBLY emphasizes open research practices, including open access, optimal research data management, early open sharing, and the involvement of knowledge actors.

The project will develop several activities, with one of its biggest milestones being the three upcoming pilot CAs: a local pilot, a national pilot, and a transnational pilot involving citizens from up to six countries across diverse regions of the European Union. EU-CIEMBLY has a duration of four years and is funded by the European Union under the Horizon Europe research and innovation program. The consortium consists of eleven partner organizations, bringing a wide range of expertise and knowledge related to the project’s scope and objectives.

The project deliverables so far:

Since the project’s launch, the team has produced:

For further information, you may visit the project’s website at www.eu-ciembly.eu and its social networks on Facebook , Instagram and Twitter. For more information on the University of Essex involvement in the project please visit https://www.essex.ac.uk/research-projects/eu-ciembly

Our project embraces multilingualism! Should an accurate translation for specific sections of this Press Release, please contact us at eu-ciembly@ij.uc.pt

This project has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon Europe research and innovation program under grant agreement number 101132694. This press release reflects only the author’s view. The Commission is not responsible for its content or any use that may be made of the information it contains.

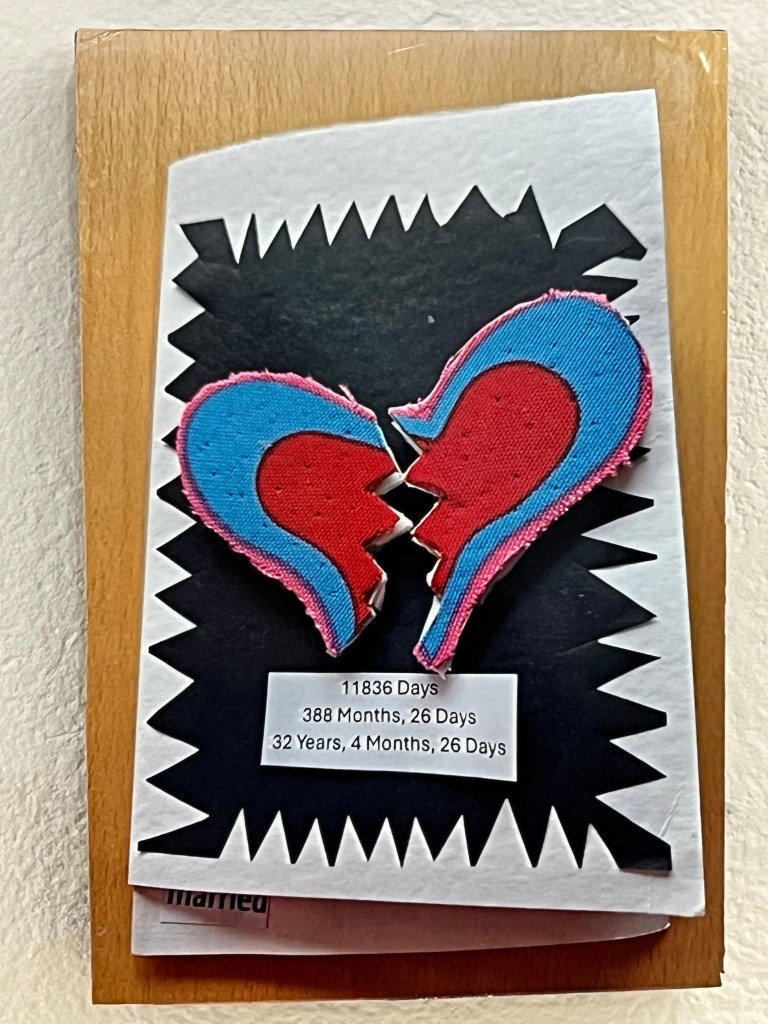

Following on from the success of last year’s Expressions of Trauma Exhibition led by Essex Healthwatch and held at The Minories, Colchester, the Essex Law School is contributing towards another exhibition, this time at the Martello Tower, Jaywick. The 2025 Expressions of Trauma provides those who missed last year’s Exhibition an opportunity to see the exhibits again – along with some new exhibits.

This thought-provoking Exhibition features diverse exhibits exploring trauma narratives. There is a dedicated installation which is based on the research of Dr Samantha Davey (University of Essex) and Dr Stella Bolaki (University of Kent), who ran a series of artist’s books workshops for mothers, which was funded by both institutions. This research highlights the experiences of mothers who have lost children through adoption, providing a powerful outlet for emotional expression. By sharing their stories through artist’s books, pictures and poetry, this exhibit encourages public awareness and empathy for mothers who suffer grief and loss, in the aftermath of adoption.

Dr Davey and Dr Bolaki would like to thank Healthwatch Essex and their research champions Chloe Sparrow, Amanda Swan and Diana Defries for their participation and ongoing support with this project and the exhibitions. There are more exhibitions planned so please do keep an eye on our blog page, the Essex communications page (you can see our press release here).

For further information about this Exhibition please contact the organiser, Sharon Westfield de Cortez, Healthwatch Essex at Sharon.westfield-de-cortez@healthwatchessex.org.uk . If you are a mother who has experienced loss through adoption and would like to know more, or to participate in future exhibitions running later this year, please contact Dr Samantha Davey at smdave@essex.ac.uk.

By Dr Koldo Casla

Dr Koldo Casla, project lead of Human Rights Local, has submitted evidence to the UN Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights for their inquiry into the state of socio-economic rights in the UK. Socio-economic rights include, among others, the right to housing, food, education, social security, health, access to work and good working conditions, all of which are recognised in the 1966 International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR).

Launched in 2020, Human Rights Local is a project of Essex Human Rights Centre to make human rights locally relevant in the UK.

Every few years, the 170+ states that have ratified ICESCR ought to report to the UN Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (CESCR) on the policies they are implementing to respect, protect and fulfil socio-economic rights. For the UK, the last review was completed in 2016. The current one began in 2022 and will end with a UN report, known as ‘concluding observations’, that will probably be published around mid-2025. This report will be based on information provided by the UK government and devolved administrations, as well as evidence from three National Human Rights Institutions (the Equality and Human Rights Commission, the Scottish Human Rights Commission and the Northern Ireland Human Rights Commission), and evidence from NGOs and academics. On 13-14 February, the UN Committee will meet with civil society groups and NHRIs in Geneva, and it will also hold a ‘constructive dialogue’ with UK government representatives.

As part of Human Rights Local, Dr Koldo Casla has provided support to community groups and people with lived experience of poverty so they could provide their own evidence to the UN and their recommendations to bring about the necessary changes to improve their lives. This is part of GRIPP (Growing Rights Instead of Poverty Partnership), of which Essex Human Rights Centre is a founding member.

In addition, Dr Casla has also conducted research for Amnesty International about the extent to which the UK’s social security system (Article 9 ICESCR) meets international standards in relation to the right to social security. The study will be published later this year, but beforehand Amnesty International will rely on the evidence and the recommendations in their advocacy with the UN Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights.

Dr Casla has also co-authored two submissions for the UN Committee. One of them identifies a series of concerns about the level of enjoyment of the right to health (Article 12 ICESCR) among Gypsy, Roma and Travelling communities in the East of England. It is based on qualitative evidence in the form of testimonies gathered in 37 peer-to-peer interviews conducted by four partner organisations – COMPAS, GATE Essex, Oblique Arts, and One Voice 4 Travellers – between June and August 2023. The evidence was part of the project “Building a community of practice to identify strengths, barriers and prioritise solutions to the right of access to healthcare for Travelling Communities”, led by colleagues in the School of Health and Social Care, and funded by the National Institute for Health and Care Research, between February 2023 and August 2024. The qualitative evidence compiled in the document is the unreserved confirmation that the UN’s concerns persist in relation to stigma, prejudice, discrimination, lack of informational accessibility and lack of cultural acceptability of healthcare for Gypsy, Roma and Traveller communities. This is reflected in the lack of cultural awareness in availability of suitable health professionals, lack of non-English language provision, problems of trust due to lack of cultural competence, lack of understanding of issues around literacy, and ongoing social exclusion, particularly digital exclusion.

The second submission goes hand in hand with the anti-poverty human rights NGO ATD Fourth World. It examines the impact of child protection services on families in poverty. Creating a social security system that guarantees the essentials in life, regulating for-profit children’s homes, and extending peer-parent support are among a list of recommendations to preserve the right to protection and assistance to the family (Article 10 ICESCR) for households living in poverty.

As argued by Dr Casla and Lyle Barker in a paper published in the Journal of Human Rights Practice in 2024, lived experience brings both epistemic and instrumental value to human rights research. In relation to the former value, in a peer-led process, people with lived experience of poverty do not simply provide evidence, data and information. Instead, they rank their concerns, frame their grievances in their own terms and decide about their priorities and the research methodology. This approach intends to address the epistemic injustice that silences people in poverty and dismisses their knowledge. In relation to the second value, the instrumental one, lived experience can help detect the real impact of the distinguishing features of specific human rights. For example, in relation to child protection services, a peer-led and participatory action research with families showed that one of the instrumental values of putting lived experience first is that it can reveal the true nature, prevalence and damage of povertyism – the negative stereotyping of people in poverty – on people in poverty.

For more information lease contact Dr Koldo Casla @ Koldo.casla@essex.ac.uk

By Essex Law Research Team

In Prohibited Force: The Meaning of ‘Use of Force’ in International Law (Cambridge University Press, 2024), Dr. Erin Pobjie addresses the ambiguities surrounding the prohibition of ‘use of force’ under article 2(4) of the UN Charter, a foundational rule of international law designed to prevent war and maintain international peace and security. Article 2(4) prohibits States from using force against each other, except in cases of self-defence or UN Security Council authorisation, yet its interpretation is often unclear in complex, real-world situations. Recognizing these challenges, Dr Pobjie introduces her ‘type theory’ framework, which suggests that determining a prohibited use of force should involve a set of contextual requirements and a flexible set of ‘non-essential’ elements – including physical force, effects, gravity, and hostile or coercive intent – that are weighed together, rather than applied rigidly. With this framework, Pobjie brings analytical depth to ambiguous cases, refining our understanding of this cornerstone of international law. Adil Haque describes Prohibited Force as ‘an extraordinary book’ with a ‘striking and rare’ combination of theoretical sophistication and empirical rigour.

Opinio Juris, a leading blog on international law, recently hosted a symposium to engage critically with Prohibited Force. The discussion opened with Dr Alonso Gurmendi’s introduction, followed by Professor Claus Kreß, who highlighted the book’s potential to strengthen the international legal order. Professor Adil Haque explored its implications for self-determination units, while Ambassador Tomohiro Mikanagi considered its relevance to cases of territorial acquisition. Professor Andrew Clapham underscored the framework’s real-world impact, noting that its insights could affect thousands of lives by shaping legal responses to blockades impacting food and humanitarian supplies in conflict zones like Yemen and Gaza. Professor James Green reflected on the strengths and potential limitations of type theory when applied to complex, borderline cases, and Professor Alejandro Chehtman highlighted the need to balance analytical sophistication with accessibility in practical settings. In her response, Dr Pobjie engaged with each contributor’s insights and critiques, underscoring her framework’s potential to foster richer discourse on the prohibition of force and its role in advancing international peace and security.

The full symposium can be read here: Symposium on Erin Pobjie’s Prohibited Force: The Meaning of ‘Use of Force’ in International Law – Introduction – Opinio Juris

Prohibited Force is available open access for all readers thanks to the University of Essex’s Open Access Fund: https://doi.org/10.1017/9781009022897

On September 20th, the Supporting Families conference was held, uniting a diverse group of speakers from various academic and professional backgrounds. The event was led by Dr Samantha Davey, a Lecturer in Law within the Essex Law School. The event was attended by academics from the University of Essex, as well as representatives from a number of other institutions including the University of Bristol, the University of Kent, with international contributors from Israel and Saudi Arabia, making it a global gathering focused on family justice. The event was kindly sponsored by Our Family Wizard.

The range of themes addressed at the conference centred on the challenges within the family justice system and explored innovative strategies for enhancing the experiences of families. The speakers presented on a wide array of issues such as legal barriers faced (for those such as litigants in person), psychological impacts of involvement in the family justice system, the growth of mediation as an important tool for families and the role of social work in supporting families to stay together and through the process of court proceedings. A presentation was delivered by Alicia Farran, a representative of the event’s sponsor Our Family Wizard, on its co-parenting app and the usefulness of online communication platforms as another tool to mediate disputes between couples in contact disputes.

The conference was chaired by Dr Laure Sauve (University of Essex), Dr Olayinka Lewis (University of Essex), Liz Fisher Frank (Director of the Essex Law Clinic), and Liverpool barrister Celeste Greenwood (Exchange Chambers), who guided discussions and facilitated insightful dialogues throughout the day. We appreciate the dedication of Katherine Rose in assisting with the setup on the day and the Essex Law Clinic students who attended this event.

Overall, the Supporting Families conference successfully brought together a multidisciplinary group of academics and practitioners in law, psychology, and social work, which led to important dialogue aimed at improving the family justice system for all users. If you have any questions about the conference or would be interested in presenting at any future events, please contact Dr Samantha Davey at smdave@essex.ac.uk .

By Dr Nikhil Gokani, Lecturer in Consumer Protection and Public Health Law, Essex Law School

Nikhil is Chair of the Alcohol Labelling and Health Warning International Expert Group at the European Alcohol Policy Alliance, Vice President of the Law Section at the European Public Health Association, and member of the Technical Advisory Group on Alcohol Labelling at WHO.

This blog is a condensed version of N Gokani, ‘Booze, Bottles and Brussels: Member States’ Dilemma on Alcohol Health Warnings’ (2024) 13(2) Journal of European Consumer and Market Law 97-102. The full article is available here. An open access version is also available here.

An example of an alcohol health warning. Pictured here as used in the Yukon Study.

Alcohol is a causal factor in more than 200 diseases, injuries and disabilities. Even at lower levels of consumption, alcohol is associated with increased risks of heart diseases and stroke, liver cirrhosis, cancers and foetal alcohol disorders. In the EU, alcohol consumption causes between 255,000 and 290,000 deaths per year. Beyond health, alcohol results in significant social and economic losses to individuals and society at large.

Despite negative consequences of drinking alcohol, consumer awareness of its harms is low. The World Health Organization (‘WHO’) has repeatedly called on States to provide consumers with essential information through alcohol labelling. The EU has itself acknowledged the importance of consumer alcohol information, reflecting the foundation of EU consumer protection policy that consumers can be empowered through becoming well informed.

EU level regulation of alcohol labelling

Current EU rules in Regulation 1169/2011 on the provision of food information to consumers (‘FIC Regulation’) require alcoholic beverages with a content over 1.2% alcohol by volume (‘ABV’) to include alcohol strength on the label. Similar health-related information, including ingredients list and a nutrition declaration, which are required on the labels of most food products, are exempt for alcoholic beverages above 1.2% ABV. EU law does not require other health-related information to appear on the label.

Health-related warnings are not explicitly addressed under EU law and several Member States have introduced national mandatory labelling rules. These have focused on two forms on messaging: mandatory label labelling relating to the age of consumption and messaging against drinking during pregnancy.

In October 2018, Ireland signed into law its Public Health (Alcohol) Act 2018. In May 2023, Ireland signed into law as its Public Health (Alcohol) (Labelling) Regulations 2023. From May 2026, non-reusable alcohol containers will be required to include the following labelling.

While feedback from civil society organisations representing public health and consumer protection expressed strong support, industry bodies from across the globe responded opposing the measure. The feedback questioned the compatibility of the Irish Regulations, and warning labelling in general, with EU law in three key ways, which are addressed in turn below.

Legal objection 1: The Irish rules constitute a discriminatory barrier to free movement

Alcohol labelling is harmonised at EU level. National labelling rules fall within the scope of the FIC Regulation. National alcohol warning labelling rules are allowed under two different sets of rules in the FIC Regulation – depending on whether or not warning labelling would be considered to be “specifically” harmonised by the FIC Regulation.

On the one hand, health warnings are not specifically mentioned in the FIC Regulation. This suggest that health warning labelling is not “specifically” harmonised. Under this interpretation, Member States may introduce national rules. This is allowed providing that these are not contrary to general EU Treaty provisions.

On the other hand, the full list of mandatory labelling particulars (eg list of ingredients, use by date) have been listed in the FIC Regulation. This suggests that the mandatory labelling has been “specifically” harmonised. Under this interpretation, Member States may not introduce national rules unless the FIC Regulation includes a derogation. The FIC Regulation does indeed include a derogation. Article 39(1) allows Member States may adopt rules requiring additional mandatory particulars justified on public health or consumer protection grounds. This is allowed providing that Member States do not undermine the FIC Regulation and that the national rules are not contrary to general EU Treaty provisions.

Therefore, irrespective of the different interpretations of the FIC Regulation, Member States seem able to move forward with national warning labelling.

Legal objection 2: The Irish rules are not consistent with existing EU harmonisation

The FIC Regulation requires that Member States may not undermine its base protection in Article 7. Therefore, national labelling shall be “accurate”, “clear and easy to understand” and “not be misleading”.

Accurate: Taking the Irish labelling as case study, this labelling is accurate according to scientific consensus. Evidence that “Drinking alcohol causes liver disease” is well-stablished. The evidence on the dangers of drinking during pregnancy is also clear. No amount of alcohol is considered safe during pregnancy. There is also well-established evidence that “There is a direct link between alcohol and fatal cancers”. Alcohol is classified as a group 1 carcinogen by the WHO International Agency for Research on Cancer.

Clear: The requirement that information is “clear” relates to legibility and visibility. The Irish warnings meet this requirement not least as they appear against a white background, are within a black box and have a minimum size.

Not misleading: The Irish labelling is also not misleading. In line with broader consumer protection in the internal market, compliance with information rules is assessed against the behaviour of the “average consumer who is reasonably well informed and reasonably observant and circumspect taking into account social, cultural and linguistic factors”. This notional average is an active player in the market who reads information, has background knowledge, is critical towards information, does not take information literally, and will not be misled easily if sufficient information is available. This average consumer is likely to understand the meaning of the Irish labelling. The pregnancy warning simply advises women not to drink during pregnancy as per national health guidance. The message that “There is a direct link between alcohol and fatal cancers” communicates association with fatal cancers but does not go as far as communicating a direct causal relationship notwithstanding the well-established evidence on causation. The warning that “Drinking alcohol causes liver disease” is not misleading as liver disease occurs with even relatively lower levels of consumption.

Therefore, the Irish rules appear compatible with existing EU harmonisation.

Legal objection 3: The Irish rules are not proportionate

National alcohol labelling must also be proportionate, which it is when it is suitable and necessary to achieve its objective.

Legitimate objective:The primary objective for warning labelling is to inform consumers. It is also a part of a broader, secondary objective of reducing consumption and harms. As the Irish Regulations have been introduced under the Article 39 derogation, the objectives are limited to “the protection of public health” and “the protection of consumers”. Alcohol control clearly falls within these broad grounds as the CJEU has consistently held.

Suitability:Under the suitability limb of proportionality, it is necessary to determine whether the proposed labelling can attain its objectives of informing consumers and contributing to a reduction in consumption as part of a broader suite of measures. In respect of the primary objective, evidence demonstrates that there is a deficit of knowledge about the health consequences of alcohol consumption and labelling informs consumers. Studies show that alcohol health warnings leads to increased knowledge of health risks. Indeed, EU law already requires certain food products to be labelled with health warnings. As regards the secondary objective, evidence shows the contribution of labelling to reduction in harms and consumption.

Necessity:Under the necessity limb of proportionality, it must be determined whether a less intrusive measure can be equally effective as the proposed labelling to attain the objectives. Other measures are not equally effective. Labelling is available at both the point of purchase and point of consumption. Labelling is available on every container. It is targeted so that everyone can see the label when they see alcohol, but its visibility is in proportion to the number of containers a person consumes. It mitigates the effect of promotional marketing messaging on labelling. Ongoing costs are minimal.

Therefore, the Irish rules appear proportionate.

The objection raised by industry, that EU food law is a barrier to national alcohol health warning labelling rules, are demonstrably wrong. Therefore, in the absence of EU level action, Member States must take responsibility for moving forward independently. Let us hope the rest of the EU follows Ireland’s lead.

Nevertheless, EU institutions must support Member States to tackle alcohol-related harm. Tides appeared to be turning with Europe’s Beating Cancer Plan, in which the Commission committed to introducing proposals on alcohol health warning labelling by the end of 2023, but the deadline passed with no action. Let us also hope the EU decides to prioritise the health of consumers over the interests of economic actors.

By Sarah Zarmsky, Assistant Lecturer, Essex Law School

Historically, international criminal law (ICL) has been mainly concerned with physically violent crimes. Progressively, ICL has begun to recognise the importance of mental forms of suffering (such as for torture and genocide), but this has always been in connection with cases focused on physical harms. Recently, developments such as the proposed addition of the crime of ecocide to the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court have signalled that ICL may be ready to evolve further and accommodate novel types of harm, including those perpetrated through technology.

To explore the potential of ICL to encompass online harms, or harmful acts perpetrated through online spaces, Sarah Zarmsky, PhD Candidate and Assistant Lecturer with the Law School, recently published her article ‘Is International Criminal Law Ready to Accommodate Online Harm? Challenges and Opportunities’ with the Journal of International Criminal Justice (JICJ). This article stems from part of Sarah’s doctoral research on accountability for digital harms under ICL, which encompasses a broader range of harms inflicted using technology than online harms.

This article aims to answer the understudied question of how technology can serve as the vehicle by which certain international crimes are committed or lead to new offences. It explores how current international criminal law frameworks may be able to accommodate ‘online harms’ to ensure that the law recognises the full scope of harms caused to victims, who currently may not be able to access redress through the international criminal justice system.

Three examples of online harm that have a foreseeable nexus to the perpetration of international crimes are identified, including (a) hate speech and disinformation, (b) sharing footage of crimes via the internet, and (c) online sexual violence. The article analyses these online harms alongside similar harms that have been encompassed by core ICL crimes, including genocide, crimes against humanity, and war crimes, to assess how they might fit into existing definitions of crimes (potentially as an aggravating factor at sentencing or as a new manner of commission), or warrant the creation of an entirely new offence.

The article concludes that the examples of online harm considered in the piece should be able to be accommodated by existing crimes, but this does not mean they should necessarily be treated the same as ‘traditional’ offences.

For example, in the case of the spread of hate speech, this online harm could likely fall under existing definitions of persecution or incitement to genocide, or when footage of crimes is shared online, it could likely amount to an outrage upon personal dignity. Yet, the online component often exacerbates the harm—for instance, posting a video of a crime could be potentially even more humiliating than committing the same crime in a public square, where the footage is not preserved, distributed, and virtually impossible to get rid of.

These elements should be recognised by ICL Chambers in future cases, such as during the gravity assessment of the crimes or at sentencing, to ensure that the full scale of the harm is acknowledged.

Finally, the article emphasises that as technology will only continue to develop and serve as a vehicle for an increasing array of harms, finding ways to account for online harm and bring redress to victims should be an issue at the forefront of ICL.

The article forms part of a forthcoming Special Issue with the JICJ edited by Dr Barrie Sander (Leiden University) and Dr Michelle Burgis-Kasthala (University of Edinburgh) titled ‘Contemporary International Criminal Law After Critique’.

The discussions that will be sparked by this article are relevant to the explorations of engaging with ICL ‘after critique’ presented in the Special Issue, as it is important that ICL be able to recognise and adapt to new forms of harm to avoid the favouring of existing criminal harms that can reinforce traditional assumptions and stereotypes behind the law.

By Dr Koldo Casla, Senior Lecturer, Essex Law School & Director, Human Rights Centre Clinic

Image courtesy Nathan Guy (CC BY-SA 2.0) https://www.flickr.com/photos/nathan_guy/2315309592

The European Committee of Social Rights (ECSR) recently published its 2023 conclusions on the rights of children, family and migrants under the European Social Charter (ESC). The European Social Charter, in its original formulation of 1961 and the revised of 1996, is the most significant treaty under the Council of Europe dealing with socio-economic rights. ECSR is the authoritative interpreter of the Charter, and it is mandated to monitor States’ compliance with it.

As part of the reporting procure, States submit reports to the ECSR about the measures they are adopting in relation to the labour marker, social security or social assistance and other policies concerning socio-economic rights. The ECSR also relies on evidence provided by civil society, unions, national human rights institutions and academics.

In 2023, specifically in relation to rights of children, families and migrant workers (Articles 7, 8, 16, 17 and 19 ESC), the ECSR adopted 415 conclusions of conformity with the Charter and 384 conclusions of non-conformity in relation to 32 European countries (EU and non-EU). One of them is the United Kingdom, with 10 conclusions of conformity and 9 of non-conformity.

In its assessment of the situation, the ECSR relied on a report I wrote with my colleague Lyle Barker as part of Human Rights Local, a project of the Human Rights Centre of the University of Essex. Conceived and developed in partnership with the anti-poverty NGO ATD Fourth World, the report “Poverty, Child Protection, and the Right to Protection and Assistance to the Family in England”, published in June 2023, called for transformative change to child services. We combined law and policy desk research, data analysis, and interviews and focus groups with a total of 33 people (28 of them female), including parents, social workers and young adults. We argued that creating a social security system that guarantees the essentials in life, regulating for-profit children’s homes, and extending peer-parent support can help to eradicate a toxic culture of prejudice and disproportionate risk-aversion in England’s child protection services.

We made the case that child protection services are not observant of the right to protection and assistance to the family, recognised in Article 10 of the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR). Article 10 ICESCR is very similar to Article 16 ESC, the right of the family to social, legal and economic protection.

Based, among other sources, on our analysis in the mentioned report, the ECSR concluded that “the situation in the United Kingdom is not in conformity with Article 16 of the 1961 Charter on the grounds that: equal treatment of nationals of other States Parties regarding the payment of family benefits is not ensured due to the excessive length of residence requirement; the amount of child benefits is insufficient.”

Between 2022 and 2025, the UK is also being examined by the UN Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, which monitors compliance with ICESCR. In December 2022, we submitted a summary of the preliminary conclusions to the UN Committee. Alongside a colleague with lived experience of poverty from ATD Fourth World, I presented the submission to the UN Committee in March 2023 remotely. The Committee’s List of Issues for the UK Government included one of our concerns, which had not been addressed in any other submission, namely, the regulation and monitoring of private and for-profit providers of child protection. We will continue engaging with international human rights bodies and urging the authorities to implement the necessary measures locally and nationally to protect children and families in poverty in the UK.

Dr Koldo Casla, Senior Lecturer at Essex Law School, is a member of the Academic Network on the European Social Charter and Social Rights (ANESC), and co-editor of The European Social Charter: A Commentary, Volume 3 (2024), on Articles 11-19 ESC.

As of Tuesday 26th March 2024, the Essex Law Research Blog will be on a short hiatus for the next four weeks.

We will publish intermittently over the next weeks and will return to regular full service on 23rd April 2024 to share more research ideas and news from the Essex Law School.

– The Essex Law School Research Visibility Team