You can now find the Essex Law Research blog at its new homepage on the University of Essex blog:

Essex Law Research Team – University of Essex Blog

We look forward to welcoming you there for new posts, insights and updates from our researchers.

You can now find the Essex Law Research blog at its new homepage on the University of Essex blog:

Essex Law Research Team – University of Essex Blog

We look forward to welcoming you there for new posts, insights and updates from our researchers.

By Professor Ting Xu, Essex Law School

On 16 May 2025, Professor Ting Xu presented at the Open University’s online legal histories conference, Land and Property Beyond the Centenary, marking 100 years since the transformative property law reforms of 1925 in England and Wales. The centenary offered a rich opportunity to reflect not only on English legal history, but also to look beyond it—to consider alternative models of property governance across time and place.

Professor Xu’s presentation, ‘Beyond 1925: Households, Property, and State Governance—Comparative Perspectives from Rural China’, grew out of her recent research on Resilience, Institutional Change, and Household Property in Rural China. This work draws on Chinese legal history, interdisciplinary scholarship on resilience, and Martha Fineman’s vulnerability theory to rethink how we understand property systems, particularly in contexts that don’t conform to liberal assumptions.

For a field so often shaped by Western, individualist models, rural China offers a compelling case that challenges many taken-for-granted ideas in property law. In her presentation, Professor Xu asked: what sustains property systems under pressure? And what might English legal history gain by looking East?

The 1925 property law reforms in England and Wales were undoubtedly revolutionary. They sought to simplify and modernise a fragmented land system, advancing values such as clarity and certainty of title and ease of transfer—cornerstones of a liberal, market-oriented property regime. Yet, even within this liberal framework, English law has long recognised informal interests, especially within the household. Trusts over the family home, for example, remain one of the most contested and evolving areas in property law.

As Robert Ellickson has argued, the household operates largely through informal norms, rather than strict legal rules. These norms—based on intimacy, trust, and shared routines—are efficient and reduce the need for legal intervention. But the limits of this view become clear when we account for issues of dependency, vulnerability, and inequality—particularly in household governance.

Feminist scholars such as Martha Fineman have pushed back against the liberal ideal of the autonomous, self-sufficient property holder. Fineman’s vulnerability theory reminds us that all human beings experience dependency and vulnerability at various points in their lives, and that resilience—our ability to navigate life’s inevitable challenges—is deeply shaped by institutions and their willingness to support us.

Inspired by Fineman and Ellickson, but also moving beyond them, Professor Xu’s presentation invited the audience to shift how we think about property. Rather than focusing only on legal certainty or formal title, what if we view property as a form of adaptive governance? And what if, instead of seeing informality as a deviation or a problem, we understand it as a site of institutional adaptation (and innovation)—particularly in systems that have long relied on collective, state-controlled, or non-liberal traditions?

To explore these questions, Professor Xu turned to the rural Chinese household and its role in property governance during the 20th century. From imperial systems of collective responsibility, through Maoist collectivisation, to the post-1978 rural reforms, the household has served as a key governance unit adapted to profound ecological, socio-economic, and political transformations.

The model that crystallised in the late 1970s and 1980s was the Household Responsibility System (HRS). Under this system, rural land remained collectively owned, but the rights to use and benefit from land were contracted to individual households. These households gained control over key production decisions—like what crops to grow or how to invest, while still being part of a broader collective governance framework.

The HRS was not a spontaneous market-driven reform. It was an institutional innovation shaped by history, political negotiation, and grassroots experimentation. It was also a response to crisis: the failures of collectivised agriculture and the need to revive rural productivity without dismantling state oversight altogether.

In legal terms, the HRS is striking. It doesn’t offer private ownership in the liberal sense. Nor does it offer full certainty or enforceability by Western standards. Yet it has endured, evolved, and adapted across decades of political and socio-economic transformation.

From a resilience theory perspective—drawn from ecological and institutional scholarship—this makes perfect sense. Systems survive not because they are static or clear-cut, but because they can bend without breaking. They absorb shocks, adapt to new conditions, and renegotiate relationships among actors and institutions.

In her presentation, Professor Xu argued that property should be understood as a socio-ecological system—an evolving interaction among resources (e.g., land and housing), governance structures, and legal rights and entitlements (she calls the interaction of these three elements ‘a resilience triad’). As discussed above, what is often ignored is the governance aspect—one key component of property. In the Chinese context, the household plays a central role in this socio-ecological system. Beyond being a mere private unit, it is a resilient institution, from lineage structures and collective responsibility systems to contemporary contracting practices.

However, as Fineman’s work reminds us, we must be cautious not to romanticise informality or resilience. Systems that appear stable at the surface can mask deep inequalities.

One of the clearest examples in the Chinese case is gender. Although households contract with the collective, land contracts are often issued in the name of the male head. Women’s rights to land are frequently tied to marital and registration status. When households divide or dissolve—due to divorce or migration, for instance—women may lose access to land altogether.

This parallels, in some ways, the difficulties faced in English co-ownership disputes, where informal arrangements and non-financial contributions (such as caregiving) can be difficult to assert legally. In both contexts, legal informality without institutional support leaves vulnerable members at risk.

Resilience, then, must be understood not simply as survival or adaptation, but as something that must be supported—and made just—through institutional design. This is where Fineman’s idea of the responsive state becomes important. Whether in liberal or non-liberal contexts, property systems that work in practice are those that can support resilience equitably, not just functionally.

Presenting this work at the Open University conference sparked excellent conversations. While many in the audience were not experts on China, they immediately saw the relevance of these ideas to broader legal questions. What happens to property under conditions of uncertainty—whether ecological, economic, or political? How do communities maintain access and control when formal systems fall short?

There is no one-size-fits-all model. But the Chinese experience shows that property systems can be stable without being rigid, and adaptive without relying entirely on individual title. It also reminds us that households, communities, and informal institutions are not remnants of the past, but active sites of governance in the present.

As we reflect on 100 years since the 1925 property reforms, this moment invites us to think globally and historically. The liberal vision of property—rooted in autonomy, clarity, and marketability—has achieved many successes. But it is not the only way property works. And in an era of climate stress, displacement, and inequality, it may not always be the most resilient one.

Professor Xu’s research continues to explore how property systems evolve under pressure, and what we can learn by comparing across legal traditions and historical trajectories. She is particularly interested in how non-liberal or hybrid institutions help sustain access to land and resources—not only in China, but also in other parts of the Global South and beyond.

Legal history offers us more than a story of how we got here—it offers tools for reimagining where we might go next. As we face global challenges that affect land, livelihoods, and governance, property law will need to become more adaptive, more relational, and more responsive.

Rethinking property through resilience is one way to start.

The EU-CIEMBLY project organized an internal staff training workshop from November 4th to 6th at the Universidad Complutense de Madrid, Spain. The primary goal of the workshop was to advance and harmonize the partners’ understanding of the theoretical and analytical framework, essential for designing and implementing an inclusive and intersectional European Citizens’ Assembly (CA). The event aimed to equip the project team with both normative tools and empirical insights essential for creating an inclusive deliberative process throughout the project. Dr Anastasia Karatzia, Dr Niall O’Connor, and Dr. Sam Woodward represented at the workshop the University of Essex team, which also includes Dr. Rebecca Warren and Prof. Ileana Steccolini from Essex Business School.

The workshop’s agenda included various presentations and structured discussions designed to engage participants deeply with key project objectives. The first segment of the event provided an introduction to intersectionality, a conceptual framework that examines the interconnected nature of social categories such as gender, nationality, ability, age and more, and how they combine to affect individuals’ experiences of inequality and exclusion. Participants engaged with this concept to explore how intersectional equality, inclusion, and deliberation could be effectively applied in the design and implementation of a CA.

Following this, the participants explored the three key components of a CA which are governance and organization, sampling and recruitment, and deliberation and facilitation. Break-out group discussions were featured, where participants were divided into smaller groups to brainstorm ways to enhance intersectional equality and inclusion across the various stages of the CA. Facilitators documented the insights shared during these discussions and later presented the findings to the broader group for collective reflection.

On the second day of the workshop, four theoretical models for an intersectional CA were discussed in detail, with the understanding that these could evolve based on ongoing feedback and the evolving needs of the project. The workshop concluded with discussions on the development of the glossary with complicated terms along with a presentation of the project’s language policy to guarantee that all materials and discussions are accessible and inclusive.

A few words about the project:

The EU-CIEMBLY project started on January 1, 2024, with the main goal of creating an innovative and inclusive EU CA that addresses issues of intersectionality, inclusiveness, and equality in European Union political life. The project seeks to improve the landscape of participatory and deliberative democratic mechanisms firstly by providing an analytical framework and prototype for establishing the Assembly at the European Union level, with potential for adaptation at national and local levels of European Union Member States. The project draws on an academic and theoretical understanding of intersectionality, equality, and power relations. Furthermore, EU-CIEMBLY emphasizes open research practices, including open access, optimal research data management, early open sharing, and the involvement of knowledge actors.

The project will develop several activities, with one of its biggest milestones being the three upcoming pilot CAs: a local pilot, a national pilot, and a transnational pilot involving citizens from up to six countries across diverse regions of the European Union. EU-CIEMBLY has a duration of four years and is funded by the European Union under the Horizon Europe research and innovation program. The consortium consists of eleven partner organizations, bringing a wide range of expertise and knowledge related to the project’s scope and objectives.

The project deliverables so far:

Since the project’s launch, the team has produced:

For further information, you may visit the project’s website at www.eu-ciembly.eu and its social networks on Facebook , Instagram and Twitter. For more information on the University of Essex involvement in the project please visit https://www.essex.ac.uk/research-projects/eu-ciembly

Our project embraces multilingualism! Should an accurate translation for specific sections of this Press Release, please contact us at eu-ciembly@ij.uc.pt

This project has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon Europe research and innovation program under grant agreement number 101132694. This press release reflects only the author’s view. The Commission is not responsible for its content or any use that may be made of the information it contains.

Following on from the success of last year’s Expressions of Trauma Exhibition led by Essex Healthwatch and held at The Minories, Colchester, the Essex Law School is contributing towards another exhibition, this time at the Martello Tower, Jaywick. The 2025 Expressions of Trauma provides those who missed last year’s Exhibition an opportunity to see the exhibits again – along with some new exhibits.

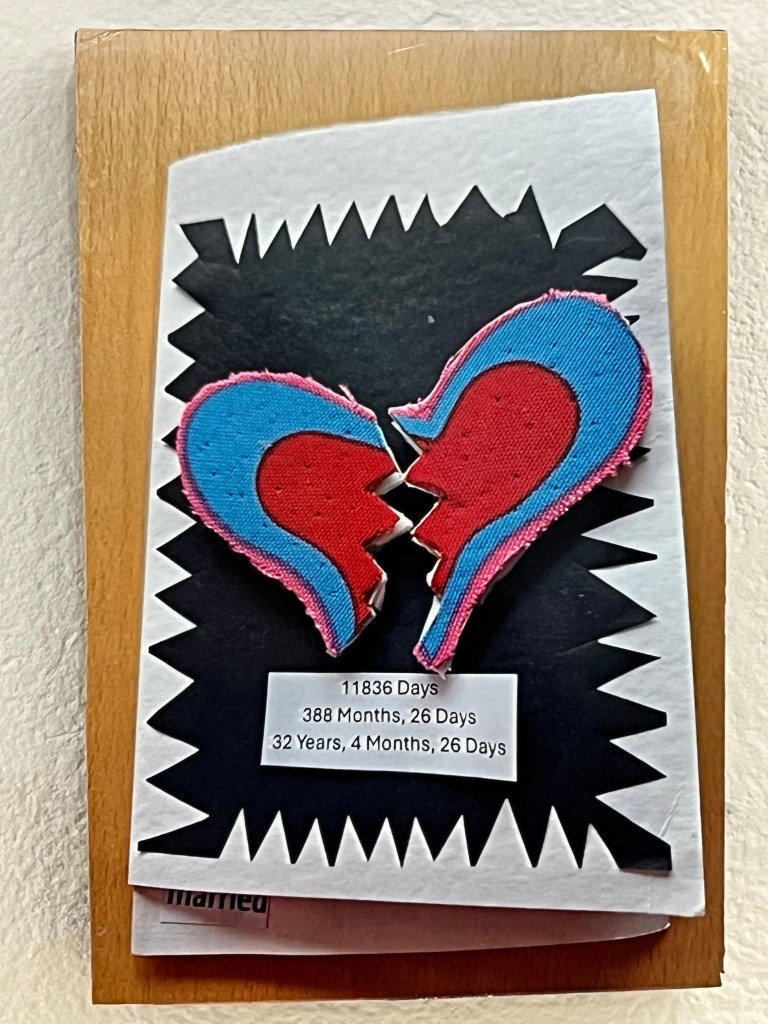

This thought-provoking Exhibition features diverse exhibits exploring trauma narratives. There is a dedicated installation which is based on the research of Dr Samantha Davey (University of Essex) and Dr Stella Bolaki (University of Kent), who ran a series of artist’s books workshops for mothers, which was funded by both institutions. This research highlights the experiences of mothers who have lost children through adoption, providing a powerful outlet for emotional expression. By sharing their stories through artist’s books, pictures and poetry, this exhibit encourages public awareness and empathy for mothers who suffer grief and loss, in the aftermath of adoption.

Dr Davey and Dr Bolaki would like to thank Healthwatch Essex and their research champions Chloe Sparrow, Amanda Swan and Diana Defries for their participation and ongoing support with this project and the exhibitions. There are more exhibitions planned so please do keep an eye on our blog page, the Essex communications page (you can see our press release here).

For further information about this Exhibition please contact the organiser, Sharon Westfield de Cortez, Healthwatch Essex at Sharon.westfield-de-cortez@healthwatchessex.org.uk . If you are a mother who has experienced loss through adoption and would like to know more, or to participate in future exhibitions running later this year, please contact Dr Samantha Davey at smdave@essex.ac.uk.

By Dr Koldo Casla

Dr Koldo Casla, project lead of Human Rights Local, has submitted evidence to the UN Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights for their inquiry into the state of socio-economic rights in the UK. Socio-economic rights include, among others, the right to housing, food, education, social security, health, access to work and good working conditions, all of which are recognised in the 1966 International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR).

Launched in 2020, Human Rights Local is a project of Essex Human Rights Centre to make human rights locally relevant in the UK.

Every few years, the 170+ states that have ratified ICESCR ought to report to the UN Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (CESCR) on the policies they are implementing to respect, protect and fulfil socio-economic rights. For the UK, the last review was completed in 2016. The current one began in 2022 and will end with a UN report, known as ‘concluding observations’, that will probably be published around mid-2025. This report will be based on information provided by the UK government and devolved administrations, as well as evidence from three National Human Rights Institutions (the Equality and Human Rights Commission, the Scottish Human Rights Commission and the Northern Ireland Human Rights Commission), and evidence from NGOs and academics. On 13-14 February, the UN Committee will meet with civil society groups and NHRIs in Geneva, and it will also hold a ‘constructive dialogue’ with UK government representatives.

As part of Human Rights Local, Dr Koldo Casla has provided support to community groups and people with lived experience of poverty so they could provide their own evidence to the UN and their recommendations to bring about the necessary changes to improve their lives. This is part of GRIPP (Growing Rights Instead of Poverty Partnership), of which Essex Human Rights Centre is a founding member.

In addition, Dr Casla has also conducted research for Amnesty International about the extent to which the UK’s social security system (Article 9 ICESCR) meets international standards in relation to the right to social security. The study will be published later this year, but beforehand Amnesty International will rely on the evidence and the recommendations in their advocacy with the UN Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights.

Dr Casla has also co-authored two submissions for the UN Committee. One of them identifies a series of concerns about the level of enjoyment of the right to health (Article 12 ICESCR) among Gypsy, Roma and Travelling communities in the East of England. It is based on qualitative evidence in the form of testimonies gathered in 37 peer-to-peer interviews conducted by four partner organisations – COMPAS, GATE Essex, Oblique Arts, and One Voice 4 Travellers – between June and August 2023. The evidence was part of the project “Building a community of practice to identify strengths, barriers and prioritise solutions to the right of access to healthcare for Travelling Communities”, led by colleagues in the School of Health and Social Care, and funded by the National Institute for Health and Care Research, between February 2023 and August 2024. The qualitative evidence compiled in the document is the unreserved confirmation that the UN’s concerns persist in relation to stigma, prejudice, discrimination, lack of informational accessibility and lack of cultural acceptability of healthcare for Gypsy, Roma and Traveller communities. This is reflected in the lack of cultural awareness in availability of suitable health professionals, lack of non-English language provision, problems of trust due to lack of cultural competence, lack of understanding of issues around literacy, and ongoing social exclusion, particularly digital exclusion.

The second submission goes hand in hand with the anti-poverty human rights NGO ATD Fourth World. It examines the impact of child protection services on families in poverty. Creating a social security system that guarantees the essentials in life, regulating for-profit children’s homes, and extending peer-parent support are among a list of recommendations to preserve the right to protection and assistance to the family (Article 10 ICESCR) for households living in poverty.

As argued by Dr Casla and Lyle Barker in a paper published in the Journal of Human Rights Practice in 2024, lived experience brings both epistemic and instrumental value to human rights research. In relation to the former value, in a peer-led process, people with lived experience of poverty do not simply provide evidence, data and information. Instead, they rank their concerns, frame their grievances in their own terms and decide about their priorities and the research methodology. This approach intends to address the epistemic injustice that silences people in poverty and dismisses their knowledge. In relation to the second value, the instrumental one, lived experience can help detect the real impact of the distinguishing features of specific human rights. For example, in relation to child protection services, a peer-led and participatory action research with families showed that one of the instrumental values of putting lived experience first is that it can reveal the true nature, prevalence and damage of povertyism – the negative stereotyping of people in poverty – on people in poverty.

For more information lease contact Dr Koldo Casla @ Koldo.casla@essex.ac.uk

By Essex Law School, written by Professor Joel Colón-Ríos

If you are an aspiring legal scholar seeking advanced training in law within a dynamic research environment that encourages innovation and interdisciplinary exploration, a Doctoral Training Partnership at Essex Law School could be your gateway to an exciting academic journey.

What are SENSS and CHASE?

The South and East Network for Social Sciences (SENSS), an ESRC-funded Doctoral Training Partnership (DTP), is dedicated to fostering innovative and inclusive social science research training and collaboration. Among the eight distinguished institutions comprising SENSS, the University of Essex plays a pivotal role as the coordinating institution.

The Consortium for Humanities and the Arts South-East England (CHASE) is an AHRC-funded Doctoral Training Partnership, providing funding and training opportunities to the next generation of world-leading arts and humanities scholars. Essex is one of the 8 world-leading institutions that comprise the membership of the CHASE DTP.

SENSS and CHASE provide fully funded doctoral studentships, mentorship from global experts, and advanced subject-specific and research methods training. These opportunities empower researchers to extend their social scientific skills beyond academia.

Here at the Essex Law School and Human Rights Centre, aspiring PhD students can apply for SENSS and CHASE studentships, unlocking comprehensive support and collaborative excellence in their academic journey.

Why choose the Essex Law School?

Choosing where to pursue your doctoral training is a significant decision. At the Essex Law School, we have meticulously crafted an environment that champions excellence and fuels innovation. Here is why you should join us:

We are a research powerhouse. Our Law School has been ranked 3rd in the UK for research power in law according to the Times Higher Education research power measure (REF2021). Law at Essex is also ranked 47th in the THE World University Rankings, which show the strongest universities across the globe for key subjects (and 9th for UK Universities). This speaks volumes about the calibre of research conducted within our School. Our academic staff collaborates globally, working with the United Nations, the European Union, governments, and non-governmental organisations.

We believe in the power of interdisciplinary research. Our dynamic research clusters foster collaboration across diverse backgrounds, creating a vibrant intellectual space for innovative and stimulating legal exploration.

With expertise spanning diverse legal disciplines, our academics are the driving force behind the Law School’s excellence. Our faculty boasts exceptional scholars, providing intellectual leadership in key areas, including Human Rights Law, led by Professor Carla Ferstman who is Director of the Human Rights Centre; International & Comparative Law led by Professor Yseult Marique, an associate member of the International Academy of Comparative Law; Private and Business Law, led by Professor Christopher Willett who also spearheads the Law, Business and Technology Interdisciplinary Hub; as well as Public Law & Sociolegal Studies, led by Professor Joel I Colón-Ríos, who is also a member of the Constitutional and Administrative Justice Initiative (CAJI). Our academic leads are ready to guide you and link you with the ideal academic mentors.

Our research student community is central to our success. These talented colleagues explore a broad range of exciting topics under expert supervision, forming a vibrant tapestry of ideas.

We asked Boudicca Hawke about her experience as a CHASE-funded doctoral student at Essex Law School.

“CHASE is a great DTP to be a part of. It is a quite a competitive funding source, but the application process itself is accessible. Especially at Essex, there’s a tremendous amount of support throughout the entire process, which really helps. There are a few rounds of revision you’ll need to go through, so it does require consistent work, but really, it’s wonderful to have guidance and support at every step so you can end with the best proposal possible.

I chose to apply primarily because of the holistic way CHASE supports affiliated doctoral researchers and encourage interdisciplinary research. Beyond the funding, CHASE also hosts annual conferences and year-round research network meetings where you can collaborate closely with other doctoral researchers who share interests but come from different universities and backgrounds. CHASE also has an incredible placement scheme, where you can get hands-on experience throughout the PhD process which is quite valuable.”

Boudicca, who is working on the status of fighters in non-international armed conflict, also shared some insights about the preparation of a research proposal: “Try to be as clear in the proposal as possible. Many of the reviewers won’t be experts in your field, so communicating the issue at-hand and value of your work in an easily digestible way is key. It can also be quite helpful to make sure you highlight relevant work experience and show why you are well-suited to do your specific project. If you don’t get it the first time around, don’t be afraid to re-apply!’’

We also talked to Matteo Bassetti, one of our SENSS-funded doctoral students. For Matteo, whose work focuses on the rights of trans people, and the underestimation of harm inflicted by States through institutional pathologisation frameworks, told us that SENSS “has contributed in many ways to my PhD experience, and has allowed me to take part to training that I would have otherwise been unable to attend. I am hoping to go on an Overseas Institutional Visit in the next term to broaden my network and horizon. However, if I have to be honest, I am still looking for more ways to use the opportunities offered by SENSS in the best way.”

He also gave us some tips about the application process: “Start ahead of time. SENSS is looking not only at the quality of the individual applicant’s proposal, but also at the match between student and supervisors. Treat your application as a collaboration between you and your supervisors, where you need to do the heavy lifting. Be prepared to modify your dream proposal to make it fit better with the selection criteria.”

Where can you find out more?

Explore the opportunities offered by the SENSS and CHASE scholarships at the Essex Law School on our informative webpages. Discover eligibility criteria, application processes, and the outstanding benefits that await you by accessing the downloadable documents provided below.

For inquiries about legal research and the SENSS and CHASE schemes, please contact Professor Joel I Colón-Ríos, our Postgraduate Research Director.

Specific questions about academic disciplines? You can also reach out directly to our dedicated Academic Leads (mentioned above) who can put you in touch with suitable supervisors.

Embark on your journey to become a world-leading scholar in law. Do not miss the chance to benefit from these funding opportunities at the Essex Law School, where innovation, excellence, and transformation define the doctoral experience.

Dr Nikhil Gokani, Lecturer in Consumer Protection and Public Health Law, University of Essex

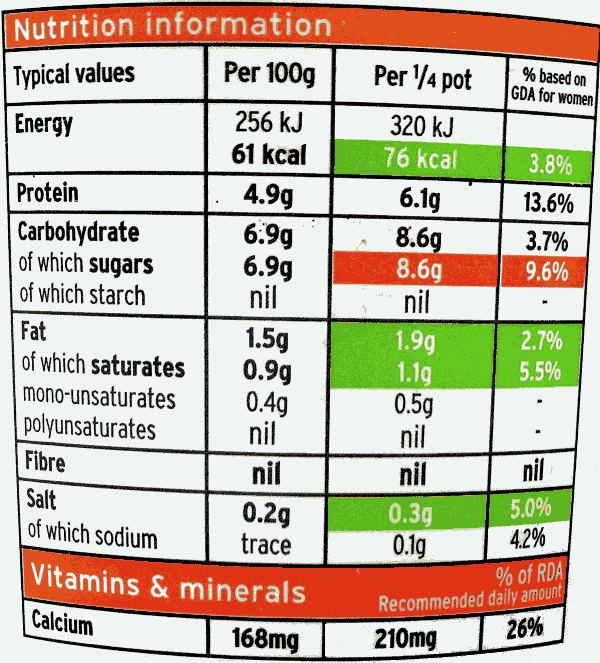

One of the main ways the EU tries to improve nutrition is to inform consumers through labelling. The Farm to Fork Strategy states that one of the EU’s objectives is “empowering consumers to make informed, healthy…food choices”. However, the current EU food information law may not be as effective in empowering consumers to make informed, healthier food choices as the EU claims.

Well-informed consumers?

EU food information rules – particularly those in Regulation 1169/2011 on the Provision of Food Information to Consumers (FIC Regulation) – seek to ensure that consumers are well-informed by giving food information that is sufficient, accurate, non-misleading, clear and easy to understand. However, EU food law does not achieve this aim.

Sufficient food information

Consumer do not actually have access to sufficient food information:

Accurate and non-misleading food information

The FIC Regulation prohibits inaccurate information. However, accurate information can still be misleading.

Mandatory labelling rules can give be misleading information:

Food labelling that is given voluntarily by manufacturers can also be misleading:

The FIC Regulation requires that food information “shall not be misleading” but even this does not prohibit all misleading information:

Clear and easy to understand food information

The FIC Regulation also requires that information shall also be “clear and easy to understand” but this is also rather ineffective:

Empowered consumers?

It is clear that EU food information rules do not inform consumers well. But, if the rules on consumer food information were improved, could such improved rules empower consumers?

To empower consumers to make healthy decisions the food environment should be conducive to consumers genuinely using health-related information. The EU is well positioned to identify features of the market that not only impede but also facilitate this. In the Consumer Agenda, the Commission stated that “empowering consumers means providing a robust framework of principles and tools” and a “robust framework ensuring their safety, information, education, rights, means of redress and enforcement”.

Research shows the factors influencing consumer food choice empowerment. These can relate to food-internal factors (eg taste), food-external factors (eg food information and physical environments), personal-state factors (eg physiological needs and habits), cognitive factors (eg skills and attitudes) and sociocultural factors (eg culture and political elements). These broader factors are not acknowledged by the Commission, which instead focusses on safety, information and education, and rights.

If food choice is a function of both multiple intrinsic consumer qualities and external environmental factors, giving consumers information is not on its own empowering them. Therefore, the EU’s strong emphasis on information regulation to empower consumers to make healthy decisions should be met with scepticism.

Information regulation as one important part of empowerment

Even if information regulation cannot, on its own, empower consumers, it is still a significant precursor to empowerment. For information to contribute to empowering consumers to make healthy food decisions, two conditions are needed.

First, the information rules should be well-designed:

Second, the limitations of information should be recognised:

Even though the EU’s strong emphasis on regulating consumer food information to improve diets is misplaced, this is not to suggest that information regulation is unimportant. Rather, it is to say that food information (i) in its current form does not lead to well-informed consumers and (ii) on its own does not empower consumers to make healthy food decisions.

Better laws that effectively address labelling as well as the other determinants are essential. We continue to call on the Commission to use its power to propose new EU laws for the benefit of consumers and their health.

This blog post is based on a more comprehensive analysis of EU food information law published in the Journal of Consumer Policy: Gokani, N., (2024). Healthier Food Choices From Consumer Information to Consumer Empowerment in EU Law. Journal of Consumer Policy. 47 (2), 271-296. It is available open access here: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10603-024-09563-0.

This post was first published on the blog of the Journal of Law and Society: https://journaloflawandsociety.co.uk/blog/meet-the-book-author-conceptualising-arbitrary-detention-power-punishment-and-control/

Conceptualising Arbitrary Detention: Power, Punishment and Control was published by Bristol University Press in May 2024.

The book is about arbitrary detention, but it is also a reflection on the shifting meaning of arbitrariness as a concept. I consider how forms of marginalisation and other arbitrary factors influence who will be detained, when, for how long and in what conditions. Policies of securitisation, regimes of exception, and criminalisation have exacerbated these arbitrary distinctions given their propensity to target “otherness,” even though there is nothing exceptional about “otherness.” How these policies are applied, and their impact on individuals and communities, depends on the underlying political values and goals at stake, which differ between countries and over time.

The book also explores how arbitrary detention has become normalised. It is used purposively by governments to foster divisions and to enforce hostility against socially marginalised groups who I classify in this book as: the “unseen” (those marginalised on account of their destitution and/or extreme social needs); the “reviled and resented” (the recipients of racist, xenophobic and discriminatory attacks); and the “undeserving” (refugees and other migrants). When arbitrary detention is normalised, it becomes impossible for courts to only countenance detention that is exceptional – the logic no longer works. So, this conundrum is analysed from different angles and factual contexts.

The idea for the book crept up on me in a non-linear way. It was always the book I wanted to write but it took some internal prodding and mental gymnastics for me to figure out how to articulate the urgency that I was feeling about the subject matter in a way that made sense on the page. So, framing the ideas, and the ideas within the ideas took time. In many ways the book is a homage to all the survivors of arbitrary detention I have been privileged to know and support, and to all the courageous human rights defenders, lawyers and psychologists who continue to work in this space.

The methodology question is never straight-forward and the sociolegal purists may want to turn away now!

My ideas about the subject matter stem from about two decades of legal practice and advocacy working with victims of torture and seeing up close the suffering people undergo while in detention. So, there was a significant evidence base from where I derived my thinking, but it was quite diffuse, deeply personal and of course, subjective.

The purpose it served in the research process was mainly to guide me with the crucial task of figuring out what themes I needed to foreground. A good example of this is the decision I took to delve into the relationship between arbitrariness and torture. I claim that the disorientation, despair, uncertainty, lack of agency that arbitrariness produces (also considering the extensive psychological literature) is so harmful psychologically that it can rise to the level of torture (all other elements of torture being present). My decision to tackle this theme stems from years of speaking with clients about how arbitrariness in and of itself, made them feel. It also helped me to work out where I wanted to situate my thinking critically on the side of key debates. An example of this is how I critically examined the caselaw on socially excluded and marginalised groups and began to confront the failure of some courts to confront the phenomenon of industrial-scale arbitrary detention.

Then, I would say there are different layers to the book, and some of these layers are more pronounced or prominent, depending on the chapter. There is a layer which is in the classic style of human rights rapportage; going through reams of testimonials and reports to locate patterns and derive meanings and using individual narratives to give context. Another layer is the analysis of how regional and international courts have addressed the phenomenon of arbitrary detention. So, there is a deep doctrinal analysis of the caselaw and how certain findings came to be. But, because much of the caselaw lacks an obvious internal coherence I also use a variety of critical legal theories, social theory, and political philosophy to help me with the task of making sense of what has little obvious internal logic.

I enjoyed the process of pulling the text together; here’s to hoping readers will find it just as enjoyable to read!

By Essex Law Research Team

In Prohibited Force: The Meaning of ‘Use of Force’ in International Law (Cambridge University Press, 2024), Dr. Erin Pobjie addresses the ambiguities surrounding the prohibition of ‘use of force’ under article 2(4) of the UN Charter, a foundational rule of international law designed to prevent war and maintain international peace and security. Article 2(4) prohibits States from using force against each other, except in cases of self-defence or UN Security Council authorisation, yet its interpretation is often unclear in complex, real-world situations. Recognizing these challenges, Dr Pobjie introduces her ‘type theory’ framework, which suggests that determining a prohibited use of force should involve a set of contextual requirements and a flexible set of ‘non-essential’ elements – including physical force, effects, gravity, and hostile or coercive intent – that are weighed together, rather than applied rigidly. With this framework, Pobjie brings analytical depth to ambiguous cases, refining our understanding of this cornerstone of international law. Adil Haque describes Prohibited Force as ‘an extraordinary book’ with a ‘striking and rare’ combination of theoretical sophistication and empirical rigour.

Opinio Juris, a leading blog on international law, recently hosted a symposium to engage critically with Prohibited Force. The discussion opened with Dr Alonso Gurmendi’s introduction, followed by Professor Claus Kreß, who highlighted the book’s potential to strengthen the international legal order. Professor Adil Haque explored its implications for self-determination units, while Ambassador Tomohiro Mikanagi considered its relevance to cases of territorial acquisition. Professor Andrew Clapham underscored the framework’s real-world impact, noting that its insights could affect thousands of lives by shaping legal responses to blockades impacting food and humanitarian supplies in conflict zones like Yemen and Gaza. Professor James Green reflected on the strengths and potential limitations of type theory when applied to complex, borderline cases, and Professor Alejandro Chehtman highlighted the need to balance analytical sophistication with accessibility in practical settings. In her response, Dr Pobjie engaged with each contributor’s insights and critiques, underscoring her framework’s potential to foster richer discourse on the prohibition of force and its role in advancing international peace and security.

The full symposium can be read here: Symposium on Erin Pobjie’s Prohibited Force: The Meaning of ‘Use of Force’ in International Law – Introduction – Opinio Juris

Prohibited Force is available open access for all readers thanks to the University of Essex’s Open Access Fund: https://doi.org/10.1017/9781009022897

The Minories, an art gallery based on the High Street in Colchester, hosted an evocative exhibition on ‘expressions of trauma’ run by Healthwatch Essex and led by Sharon Westfield de Cortez and Kate Mahoney. This exhibition delved deep into the complex layers of trauma, with a range of exhibits exploring themes such as pain, illness, abuse, grief and loss, with art being used as a medium to empower and shared the voices of those who chose to participate in the exhibition in October and November 2024.

One of the exhibits is the result of innovative research collaboration between Dr Stella Bolaki from the University of Kent and Dr Samantha Davey from the University of Essex. This research project was kindly funded and supported by both researchers’ institutions via awards designed for knowledge exchange, impact activities and public engagement.

The works included in the ‘Expressions of Trauma’ exhibition from this project are artists’ books created during specialised workshops led by Dr Bolaki. These workshops provided a safe, creative space for mothers who have suffered the painful experience of child loss via adoption proceedings. Many participants shared their personal narratives, crafting their stories into tangible art forms that speak to their emotional journeys through care and/or adoption proceedings and in the aftermath of those legal processes.

The artists’ books featured are a powerful reflection of each of these mothers’ experiences. Each page contains raw emotions and displays feelings of love, grief, sadness, anger, frustration and, ultimately, resilience. Through art, these mothers have found a way to express pain and connect with others facing similar struggles. This powerful element of storytelling through art is what made the ‘Expressions of Trauma’ exhibition not just an art display but a shared space for dialogue between mothers, professionals and the wider public – as well as a space for reflection, healing and social justice. One of the books included showed an image from the Disney film, Dumbo, the elephant who was separated from his mother. This image is accompanied by the haunting lyrics of ‘Baby Mine’, highlighting the raw grief and loss experienced because of the separation of mother and child. Diana Defries, spokesperson at Movement for an Adoption Apology, has a book titled ‘An Ocean Between Us’, poignantly representing the gulf between a mother and child over many years.

This exhibit also highlights the importance of the roles played by professionals who support these mothers. Barrister Sneha Shrestha, local art therapist Chloe Sparrow, and Kent-based counsellor Amanda Swan contributed their insights and expertise, showing how the artist’s book can assist professionals as well, as a tool in processing trauma. Chloe Sparrow’s emotive painting of a mother and child features prominently in the exhibition, capturing the essence of the bond that endures even in loss.

This exhibit demonstrates acutely that healing is not a solitary journey; it is often facilitated by the connections we make with others personally and professionally. The inclusion of professionals in this dialogue makes the narrative of the exhibit more powerful, adding layers of understanding and compassion, showing how professionals themselves connect with the raw grief experienced by mothers.

Visitors are encouraged to engage with the stories behind the books. Each artist’s book is a book of emotion, inviting reflection and empathy from anyone who encounters it. The exhibition encouraged a sense of community and shared experience, helping attendees to understand and empathise with those who have experienced loss in a range of contexts – loss of love, loss of one’s autonomy and loss of identity.

‘Expressions of Trauma’ was not just an artistic endeavour; it was a compelling invitation to explore the landscape of human emotion. Through this exhibition, Sharon Westfield de Cortez and Kate Mahoney created an important ongoing conversation around trauma, loss, and the healing power of art.

In a world where discussions about mental health and trauma are becoming increasingly prominent, ‘Expressions of Trauma’ boldly speaks to the power of storytelling through art. The exhibition challenged visitors to confront difficult emotions and inspires them to engage with the narratives of others from different walks of life with a vast range of life experiences.

For any questions about ‘Expressions of Trauma’, please contact Sharon at sharon.westfield-de-cortez@healthwatchessex.org.uk and Kate at kate.mahoney@healthwatchessex.org.uk .

For individuals who have been affected by issues explored within the artist’s book exhibit or have any questions about the research project out of which it emerged, please contact Dr Stella Bolaki at s.bolaki@kent.ac.uk and Dr Samantha Davey at smdave@essex.ac.uk .