Dr. Haim Abraham, Lecturer in Law, University of Essex

Follow Dr. Abraham on Twitter here

The last round of belligerency between Hamas and Israel claimed a significant toll from civilians, with many arguing that some of the more devastating activities conducted by the IDF were in breach of the laws of war (for example, here, here, and here). Just days before a ceasefire was declared, Judge Shlomo Friedlander of Israel’s Be’er Sheva District Court released his ruling in the case of The Estate of Iman Elhamtz v. Israel, dismissing a claim for compensation for the killing of a 13 year old girl from the Gaza Strip by IDF forces in 2004. At first glance, this case seems to be just another instance in which the state’s immunity from tort liability for losses they inflict during combat is reaffirmed. However, a closer examination reveals that it is a significant development of the immunity, which could have vast ramifications for Palestinians’ ability to obtain compensation for losses they sustained from IDF activities that were in breach of the laws of war. Currently, Israel is immune from tort liability for losses it inflicts during battle, even if combatants inflicted the loss negligently. Yet, Judge Friedlander seems to expand the immunity further so that it applies not only to combatant activities that comply with the laws of war, but also to war crimes. This approach to the immunity has yet to be considered by the Supreme Court, but it is in stark opposition to international trends towards the scope of state’s immunity from tort liability.

The Elhamtz Case

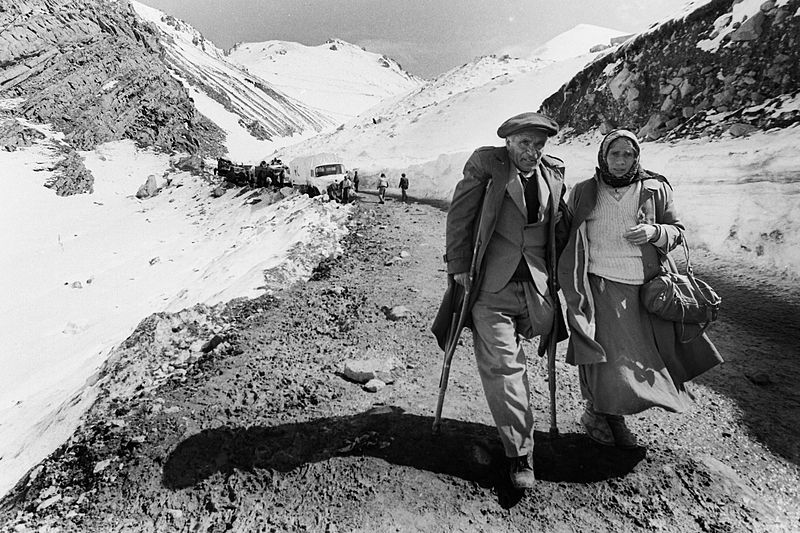

The tragic events that resulted in Iman Elhamtz’ death unfolded in 2004 while Operation “Days of Penitence” was being conducted in the midst of the Second Intifada. An IDF military post at south Gaza Strip near Rafah was under high alert against threat of attack. Elhamtz approached the post, but the lookout did not properly execute his duties resulting in Elhamtz reaching within 100 meters of the post before being detected. Surprised and, according to their testimony, fearing that she is there as a part of a terrorist activity, soldiers began shooting towards Elhamtz even as she was fleeing. Elhamtz was killed. Major R, who was the commanding officer at the time, charged her dead body and engaged in ‘dead-checking’. A total of 20 bullets were found in her body.

A military court exonerated Major R of criminal wrongdoing. Elhamtz’ estate sought a ruling that would hold Israel accountable for her death through civil proceedings, and filed a tort law-suit against Israel in the Be’er Sheva District Court in 2005, arguing that she was shot and killed negligently and in violation of international humanitarian law.

In May 2021, the court dismissed their claim, despite finding that the military force indeed acted negligently and in violation of international humanitarian law. Judge Friedlander found that the military force was negligent on two counts. First, the lookout failed to perform his duties. If he was not preparing for a shift change but had properly observed the post’s surroundings, Judge Friedlander held, Elhamtz could have been spotted from a greater distance, chased away and probably would still be alive today. Second, the immediate and excessive use of force when there was no clear threat was in breach of the rules of engagement. The court adopted these rules to determine the relevant standard of care that is expected from a military force under such circumstances and held that this standard was breached. The military force should not have fired on Elhamtz to begin with, should have stopped when she began to flee, and dead-checking was completely incompatible with the standard of care that is expected from combatants.

The court also held that the actions of the military force violated the principle of proportionality. The sheer fact that Elhamtz was near the post, according to Judge Friedlander, does not mean that combatants can use deadly force against her. Even if she posed a risk, which was highly doubtful, she should have been chased away or restrained, not killed.

The sole reason for which Israel was not held liable for the death of Elhamtz was that Israel, like many other countries, has a special immunity from tort liability for losses it inflicts during armed conflict called the ‘combatant activities exception’. Through his opinion, Judge Friedlander paved the way to reject future tort claims that are likely to be filed by Palestinian casualties from the most recent round of fighting. But to understand the legal mechanism that allows this reality, a better appreciation of the immunity is needed.

The Combatant Activities Exception

In the mid-20th century, states began reforming laws concerning their immunity from tort liability, by removing procedural and substantive hurdles for filing claims, as well as limiting the scope of the doctrine of sovereign immunity to enable holding foreign states liable in tort. Nevertheless, while immunity from liability became more limited, it was not done away with altogether. Some pockets of immunity remained, including the combatant activities exception, which, essentially, provides a blanket immunity from tort liability for wrongful actions conducted in battle.

The scope of the combatant activities exception varies between jurisdictions. Canada, for example, has what appears to be the broadest statutory exception, which precludes liability for “anything done or omitted in the exercise of any power or authority exercisable by the Crown, whether in time of peace or of war, for the purpose of the defence of Canada or of training, or maintaining the efficiency of, the Canadian Forces.” The U.S. statutory exception is somewhat more limited in its scope, maintaining that no liability would be imposed in “any claim arising out of the combatant activities of the military or naval forces, or the Coast Guard, during time of war.”

When Israel first enacted its version of the combatant activities exception through the Civil Wrongs (State Liability) Act 1952, it was very similar to the U.S. exception, simply stating that Israel is not “liable in tort for a combatant activity committed by the Israel Defense Forces.” Initially, courts interpreted the exception narrowly, holding that it is applicable only to activities in which there was an objective and immediate risk that is of a combatant character. However, with each major conflict with the Palestinian population, the scope of the exception was expanded through judicial interpretation and by legislative amendments. These expansions have three notable themes.

First, the boundary between combatant and non-combatant activities has been blurred. During the First Intifada (1987-1993), IDF forces faced large-scale violent protests. Policing operation within the Occupied Palestinian Territories exposed the forces to imminent risk to their lives, and courts were torn between a narrow and a broad interpretation of the combatant activities exception. The narrow approach ruled out the exception’s applicability, holding that policing activities are not combatant activities, even if they are conducted by military forces who are exposed to considerable risks. The broad approach held the contrary view, finding that the exception is applicable even for policing activities due to the real risk to soldiers’ lives, who were operating in a hostile environment. Ultimately, the broad interpretation of the combatant activities exception was adopted by the courts and the legislature, expanding the scope of the exception to include policing and counter-terrorist activities. The exception became so broad that it currently applies to activities in which a soldier subjectively (and mistakenly) feels at risk, as were the circumstances that led Judge Friedlander to hold that Israel cannot be held liable for the killing of Iman Elhamtz.

Second, non-Israeli Palestinians are viewed as ‘the enemy’, and their tort claims are thought of as a continuation of terrorist activities through civilian means. For example, in 2005 the Israeli parliament sought to expand the scope of the exception to include any and all injuries in the Occupied Palestinian Territories, whether combatant or not. This legislation was struck down by the Supreme Court on the grounds of it being unconstitutional. Similarly, a 2012 amendment expanded the applicability of the exception to all non-Israeli residents of the Occupied Palestinian Territories, regardless of the character of the activities that resulted in the loss (this legislation is currently being reviewed by the Supreme Court).

Third, the temporal and geographical distinction between war and peace has been undermined. The original interpretation and definition of the exception meant that it was applicable only to engagement in actual hostilities. The courts examined the circumstances that resulted in the injury, analyzing the particular location in which the activity took place, taking into account a small window of time before or after it. Following the events of the Second Intifada (2000-2005), as well as the legislative expansion of the exception, courts consider an ever-increasing context. Courts no longer examine just what happened on the particular street and time in which someone was injured. Instead, they refer to the general area and history to deduce whether combatants faced a risk that would fall under the scope of the exception, sometimes expanding the timeframe to years prior to the activity that resulted in the injury itself.

The overall effect of the expansion of the combatant activities exception resulted in a dramatic decrease in the number of tort suits being filed, from thousands of cases in the early 2000s to a handful of cases a year currently, and a finding of liability against Israel is nearly impossible. Nevertheless, the scope of the exception is still being contested by plaintiffs, and it is far from clear that its current form can be Justified (see, for example: here, here, here, and here).

‘Testing the Waters’

The dismissal of the Elhamtz case coincided with the growing criticisms of Israel’s violations of the laws of war during the 2021 round of belligerency between Hamas and Israel. These should have been two unrelated matters. One revolved around a tragic incident in 2004, the other was still ongoing in May 2021. Yet, Judge Friedlander’s opinion, which held that the exception applies not only for the military’s negligent actions, but also for its actions that violate international humanitarian law, seems to create a link between the two. In the obiter, Judge Friedlander gave contrasting examples to illustrate the limits of the combatant activities exception, noting that even if one country indiscriminately and disproportionately bombs the civilian population of another country during an armed conflict, it is a combatant activity for which the exception applies.

Judge Friedlander did not need to use this example to reach the conclusion that the exception applies. The Supreme Court has ruled years ago that claims for compensation for violation of international law should be pursued through separate proceedings, not through tort claims, and that the exception applies even for negligent injuries by the IDF. Invoking this particular example at that particular time does not appear to be a redundant hypothetical, but rather laying the groundwork for dismissing future claims that are bound to be filed against Israel for the losses it inflicted in 2021.

The Supreme Court has yet to give clear guidance on whether the combatant activities exception can apply when the State’s actions are in clear violation of the laws of war. There is a growing trend in the international community to limit the availability of states’ immunities in such cases. If the Supreme Court of Israel was to adopt Judge Friedlander’s approach, it will be expanding the scope of the combatant activities exception significantly, blurring the line between legitimate combatant activities and criminal activities. Such an interpretation appears to contradict the position that was raised in several obiters by Israeli courts. On various occasions, courts clarified the limits of the combatant activities exception by stating that criminal activities, such as looting, do not fall under the combatant activities exception even when they are done on an active battlefield. It is hard to find a rationale that will allow for an imposition of tort liability for looting property but not for committing war crimes. Neither is a legitimate act of war, and both should be excluded of the dispensations that accompany sanctioned warfare.

This post first appeared on the Blog of the European Journal of International Law and is reproduced on our research blog with permission and thanks. The original article can be accessed here.