Dr Nikhil Gokani, Lecturer in Consumer Protection and Public Health Law, University of Essex

One of the main ways the EU tries to improve nutrition is to inform consumers through labelling. The Farm to Fork Strategy states that one of the EU’s objectives is “empowering consumers to make informed, healthy…food choices”. However, the current EU food information law may not be as effective in empowering consumers to make informed, healthier food choices as the EU claims.

Well-informed consumers?

EU food information rules – particularly those in Regulation 1169/2011 on the Provision of Food Information to Consumers (FIC Regulation) – seek to ensure that consumers are well-informed by giving food information that is sufficient, accurate, non-misleading, clear and easy to understand. However, EU food law does not achieve this aim.

Sufficient food information

Consumer do not actually have access to sufficient food information:

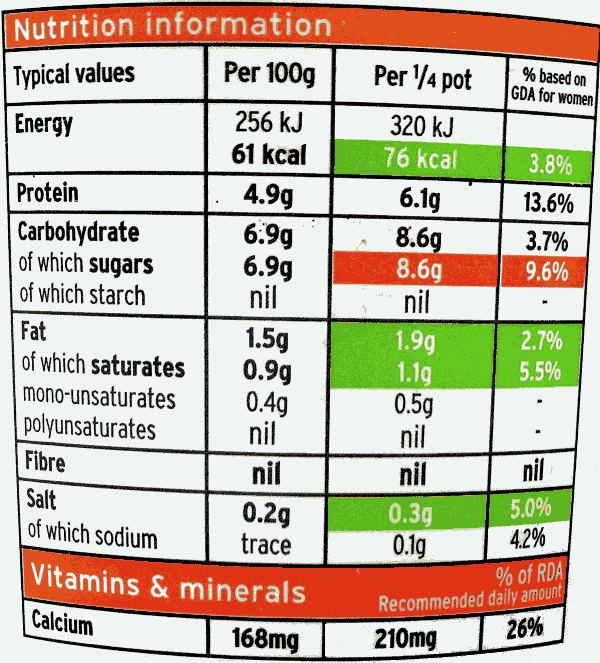

- Nutrient content must be declared per 100g/ml as sold. This helps consumers compare similar products because similar products may have comparable water content or portion sizes. It is less helpful for different product types. Information per portion would help but there is no requirement to provide nutrition information per portion. Indeed, there is also no requirement to provide information on recommended portion sizes, which is concerning because consumers are now eating larger portions. It is also does not give an interpretive guidance, as front-of-pack nutrition labelling would do.

- Ingredients are listed but the actual quantity of an ingredient is not required unless the ingredient is emphasised on the labelling. For instance, consumers may be aware that a product contains fruit, but they will not necessarily learn the quantity of fruit. Similarly, health consequences of unhealthy ingredients are not displayed.

- Mandatory particulars are only required on packaging and on sales websites. Purchase intentions are, however, also influence by advertising, but information is not required on advertising.

- There are many exemptions. Most mandatory particulars are not required for products in smaller packaging. A nutrition declaration is not required for 19 products or product categories. Most inexplicably, alcohol (which is defined as food in EU law) is exempt from nutrition or ingredients labelling.

Accurate and non-misleading food information

The FIC Regulation prohibits inaccurate information. However, accurate information can still be misleading.

Mandatory labelling rules can give be misleading information:

- The nutrition declaration may also be expressed as a percentage of consumers’ reference intake. However, percentage of reference intake can be misleading because it is a nominal value based on the needs of an average adult female. It is, therefore, inaccurate for most of the population, including many women.

- Where nutrition information is given per consumption unit, this can also be misleading because a single consumption unit (such as one square of a chocolate bar) may not reflect a portion size (such as an entire chocolate bar).

Food labelling that is given voluntarily by manufacturers can also be misleading:

- Nutrition and health claims provide positive information about the nutritional or health effects of a food product. They must be accurate and non-misleading as per Regulation 1924/2006 on Food Claims. However, even accurate food claims may be misleading. For instance, the claim that “iron contributes to the reduction of tiredness and fatigue” may be used without any explicit requirement to mention that this is only true if there is inadequate dietary intake.

- Nutrition and health claims can also be misleading. For instance, children’s cereal with significant levels of added sugars can be labelled with promotional claims such as “high in fibre” or “contains calcium”. Consumers over-generalise the positive qualities of claims, which creates a health halo, leading consumers to think that products are healthier than they are.

The FIC Regulation requires that food information “shall not be misleading” but even this does not prohibit all misleading information:

- Whether or not information is misleading is assessed using the benchmark of the “average consumer”. This is a notional, rational consumer who is “reasonably well informed and reasonably observant and circumspect”. One difficulty with this is the inconsistency between the assumed behaviour of the “average consumer” and the actual behaviour of consumers. For instance, behavioural economics shows that consumers prefer stability, form habits, have limited cognitive capacity and often evaluate only the most salient information. Even if consumers do make rational choices, rational choices are not necessarily healthy choices. For example, a single parent working full-time on a low income may rationally choose to purchase food that is locally available, has high energy per unit cost and is quick to prepare, even if this might be less healthy.

Clear and easy to understand food information

The FIC Regulation also requires that information shall also be “clear and easy to understand” but this is also rather ineffective:

- “Clear” does not mean noticeable. For instance, the mandatory nutrition declaration may appear on the back of packaging, where it is less noticeable. Essential information can also be illegible as the minimum character height of mandatory particulars can be less than 0.9mm

- Voluntary information shall “not be displayed to the detriment of the space available for mandatory food information”. However, marketing messages on labelling – such as prominent cartoon characters or bright colours – can be distracting and detrimental to the noticeability of mandatory food information.

- Even the requirement that food information is “easy to understand” is not that helpful. For instance, consumers should understand the amount of fat in a product but not whether is a healthy level or not.

Empowered consumers?

It is clear that EU food information rules do not inform consumers well. But, if the rules on consumer food information were improved, could such improved rules empower consumers?

To empower consumers to make healthy decisions the food environment should be conducive to consumers genuinely using health-related information. The EU is well positioned to identify features of the market that not only impede but also facilitate this. In the Consumer Agenda, the Commission stated that “empowering consumers means providing a robust framework of principles and tools” and a “robust framework ensuring their safety, information, education, rights, means of redress and enforcement”.

Research shows the factors influencing consumer food choice empowerment. These can relate to food-internal factors (eg taste), food-external factors (eg food information and physical environments), personal-state factors (eg physiological needs and habits), cognitive factors (eg skills and attitudes) and sociocultural factors (eg culture and political elements). These broader factors are not acknowledged by the Commission, which instead focusses on safety, information and education, and rights.

If food choice is a function of both multiple intrinsic consumer qualities and external environmental factors, giving consumers information is not on its own empowering them. Therefore, the EU’s strong emphasis on information regulation to empower consumers to make healthy decisions should be met with scepticism.

Information regulation as one important part of empowerment

Even if information regulation cannot, on its own, empower consumers, it is still a significant precursor to empowerment. For information to contribute to empowering consumers to make healthy food decisions, two conditions are needed.

First, the information rules should be well-designed:

- For mandatory labelling, the EU needs to reflect on developing evidence-based and context-sensitive rules on whether consumer information is provided, what is provided, where and when, and how it is provided. For instance, nutrition information should be provided in a way that allows consumers to understand it, such as through mandatory front-of-pack-nutrition labelling. Even though the Commission committed to proposing harmonised front-of-pack nutrition, it continues to miss its 2022 deadline.

- Regulating voluntary information more effectively is also essential. Food claims should be prohibited for less healthy products, as should other food marketing designed to or having the effect of increasing the recognition, appeal or consumption of unhealthy food.

Second, the limitations of information should be recognised:

- How consumers make food decisions is multifactorial and complex. In recent decades, it has become clear that unhealthy diets demand tackling the commercial determinants of health that drive poor nutrition. These industry practices are designed to maximise product sales by encouraging individuals to over-consume unhealthy food at the expense of healthy food. This includes creating new, highly palatable products, promoting them aggressively, selling them at lower prices than healthy food, packaging them in large ready-to-eat portions and selling them in widely accessible locations.

Even though the EU’s strong emphasis on regulating consumer food information to improve diets is misplaced, this is not to suggest that information regulation is unimportant. Rather, it is to say that food information (i) in its current form does not lead to well-informed consumers and (ii) on its own does not empower consumers to make healthy food decisions.

Better laws that effectively address labelling as well as the other determinants are essential. We continue to call on the Commission to use its power to propose new EU laws for the benefit of consumers and their health.

This blog post is based on a more comprehensive analysis of EU food information law published in the Journal of Consumer Policy: Gokani, N., (2024). Healthier Food Choices From Consumer Information to Consumer Empowerment in EU Law. Journal of Consumer Policy. 47 (2), 271-296. It is available open access here: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10603-024-09563-0.